(Source: TED Talk—Marla Spivak on ‘Why bees are disappearing’)

This small bee is holding up a large mirror.

Nearby is the country they call life.

‘Go to the Limits of Your Longing’—Rainer Maria Rilke

God speaks to each of us as he makes us,

then walks with us silently out of the night.

These are the words we dimly hear:

You, sent out beyond your recall,

go to the limits of your longing.

Embody me.

Flare up like a flame

and make big shadows I can move in.

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.

Don’t let yourself lose me.

Nearby is the country they call life.

You will know it by its seriousness.

Give me your hand.

Book of Hours, I 59

(Source: Book of Hours by Rainer Maria Rilke, Image by Elizabeth Knowles)

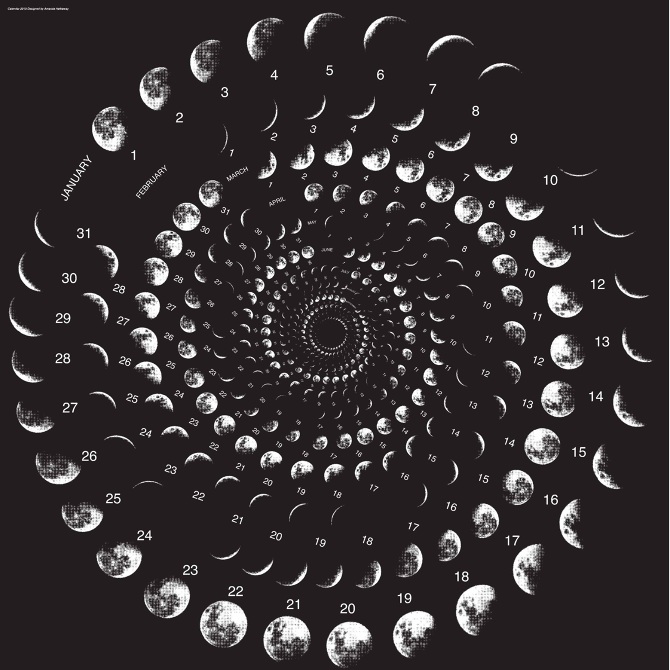

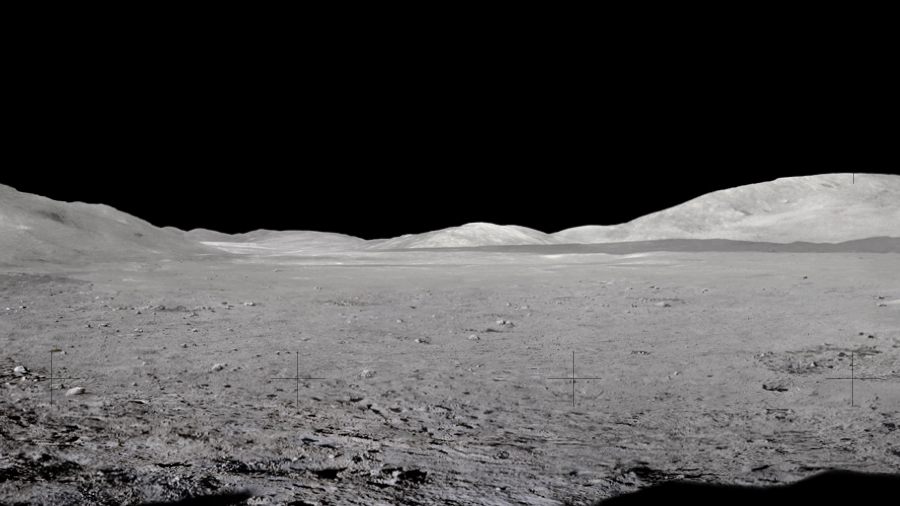

“Sun is possible”

The traditional Inuit calendar had moon-months, named for events in the land’s cycles. In his book, The Arctic Sky, John MacDonald details the Igloolik calendar which begins the year with “Sun is possible” (mid-January) and moves through the rest of the thirteen moon-months: “Sun gets higher”; “Premature birth of seal pups”; “Birth of seal pups”; “Birth of bearded seal pups”; “Caribou calves”; “Eggs”; “Caribou sheds hair”; “Caribou hair thickens”; “Velvet peels from caribou antlers”—more poetic than October, right?—then “Makings of winter”; “The hearing month” and “The great darkness.” (By “The hearing month,” at about the end of November, the seas are frozen and all ice strong enough for people to travel by dog-team to scattered camps, where people would visit and hear news of their neighbors.) Through this transparent calendar, one can “see” the landscape. The white (Western) calendar, though, hangs like thick blank white paper, preventing you from seeing the land.

(Source: Wild—Jay Griffiths, Image—Amanda Hathaway)

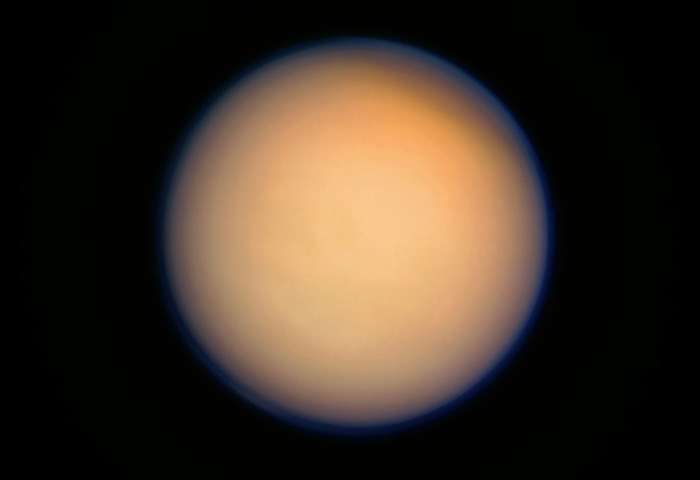

What flavour is the moon? Cool water.

The previous night, I had been the jaguar’s apprentice and the first thing I learnt was how my body felt. This night, I learnt how to mother my jaguar-self into being, in the agony and ecstasy of birth. When, with one last effort, the process was complete, the first thing I did was sniff myself. I smelt of meat and musk and damp hot fur. Jaguar, in groin, pelt and whisker, panting and alert.

I was willful, I was hungry, I was solitary, I was proud. The jaguar walks its own sure way, treads its own path with certainty and a tender ferocity. Beyond love, hate or complexity, things fell into two categories, those on the side of death and the wasteland, and those who walk with the jaguar on the side of life and the wild. From a longer for life, I roared myself into being and now sheer life brimmed me to overflowing.

“We can send you to the stars,” one of the shamans had said to me. (They were pleased because they felt I had an aptitude for ayahuasca, that I could use it and learn from it, and from what they could teach me.) And now, in my hallucinations, I saw the stars and leapt for them, pouncing from star to star until I wanted to lick the moon. So I did. The crescent moon, like a slice of white papaya, was small enough to be held in one paw. I caught it gently with my claws and licked its wet smoothness with my rough tongue. What flavour is the moon? Cool water.

(Source: Wild—Jay Griffiths)

Life on the Leaf Edge

The long summer has taken its toll on a once lush New England leafscape. What was initially strong, green, and uniform is now decorated with burnt withered edges, pot-marked with spots of fungus and decay, speckled with the galls of tiny insects, and fragmented after a sustained onslaught from a myriad of herbivores. The perfect leaf image that we might hold in our minds rarely exists in nature, instead we find that any stand of late season foliage is a war-torn mosaic of consumption and infection.

(Source: Samuel Jaffe—’Notodonta species on aspen leaf’)

a certain slant of light

We think of twilight as the mingling of the day and the night, a breathing space, sometimes calm, sometimes menacing, in which neither light nor dark prevails. But the name suggests something odder and more specific than this: not the meeting of light and dark, but rather the copresence of two different lights. As the sun sinks, its light is not steadily withdrawn, but subject to a scattering by the air and dust of the atmosphere. For a short period, this creates a strange, faint flaring of the air, an oblique blaze in things. During the hours of daylight, we have the sun always in mind, even when it is behind a cloud or at our backs. Another word for twilight is ‘gloaming’, which perfectly alloys gloom with glow. The glow of the gloaming, after the sun has gone but something of its light still lingers, seems dispersed or sourceless, as though aching evenly from every surface, as though brightness were falling from the air itself. Evocations of twilight often reach for the ambivalent colours of precious stones, pearl, opal, sapphire, amethyst, which suggest an eerie kind of earthlight, as though objects themselves were giving out their own illumination, stored during the day and given off as day retreats. As the contours of the visible world melt, other, more diffusive senses, start to leak into the eye: touch, hearing, smell.

[…]

The slight tipsiness of the earth’s solar orbit makes twilight a Northerly phenomenon. Twilight is not the time of inversion, the world turned upside down; it is time on a tilt. Perhaps it produces sensibilities that weary soon of straight-up-and-down things, of once-and-for-all, four-square perpendicularities, are inclined to see things anamorphically aslant, and have a taste for the late, the not-quite, the trick of the light, the all-but, the betwixt and between. This refractory wryness, or angled Saxon attitude, prizes what pales yet persists, what lingers and lasts out, over the blaring conflagrations of noon. Emily Dickinson, who was one such ember spirit, wrote of

a certain slant of light,

On winter afternoons,

That oppresses, like the weight

Of cathedral tunes.

Heavenly hurt it gives us;

We can find no scar,

But internal difference

Where the meanings are.

(Source: A Certain Slant of Light—Steven Connor. A sound-essay on the idea of twilight, broadcast on BBC Radio 3’s Nightwaves, October 31, 2003.)

The human body is really quiet for everything it does

“The room contains a few dozen living human bodies, each one a big sack of guts and fluids so highly compressed that it will squirt for a few yards when pierced. Each one is built around an armature of 206 bones connected to each other by notoriously fault-prone joints that are given to obnoxious creaking, grinding, and popping noises when they are in other than pristine condition. This structure is draped with throbbing steak, inflated with clenching air sacks, and pierced by a Gordian sewer filled with burbling acid and compressed gas and asquirt with vile enzymes and solvents produced by the many dark, gamy nuggets of genetically programmed meat strung along its length. Slugs of dissolving food are forced down this sloppy labyrinth by serialized convulsions, decaying into gas, liquid, and solid matter which must all be regularly vented to the outside world lest the owner go toxic and drop dead. Spherical, gel-packed cameras swivel in mucus-greased ball joints. Infinite phalanxes of cilia beat back invading particles, encapsulate them in goo for later disposal. In each body a centrally located muscle flails away at an eternal, circulating torrent of pressurized gravy. And yet, despite all of this, not one of these bodies makes a single sound at any time during the sultan’s speech. It is a marvel that can only be explained by the power of brain over body, and, in turn, by the power of cultural conditioning over the brain.”

(Source: Neal Stephenson—Cryptonomicon, Reddit.com—Shower Thoughts)

For me, a void is also a place.

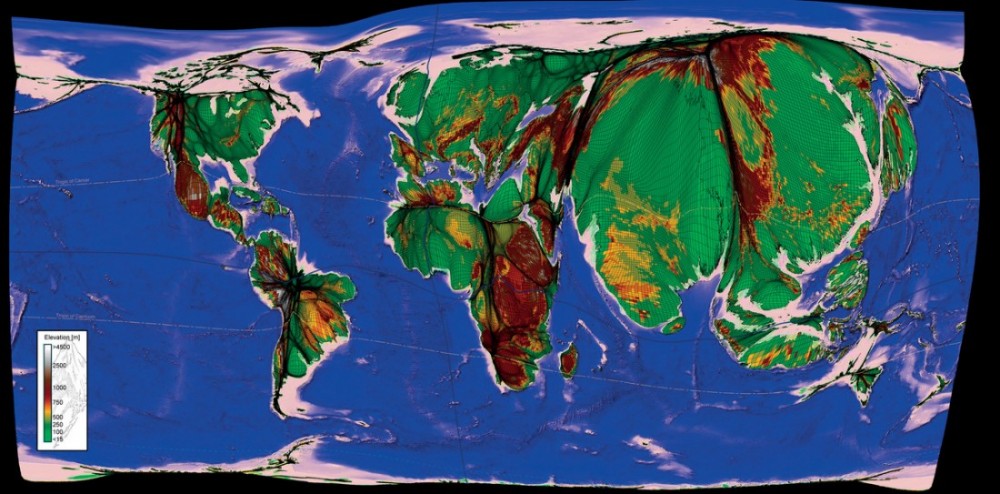

↑ A New World Population Cartogram with Topography—Benjamin D. Hennig

‘Shapes don’t automatically register as places, and cropping or figure/ground ambiguity only makes things worse. For me, a void is also a place.’—Pae White

From the Brain of a Writer—Etel Adnan

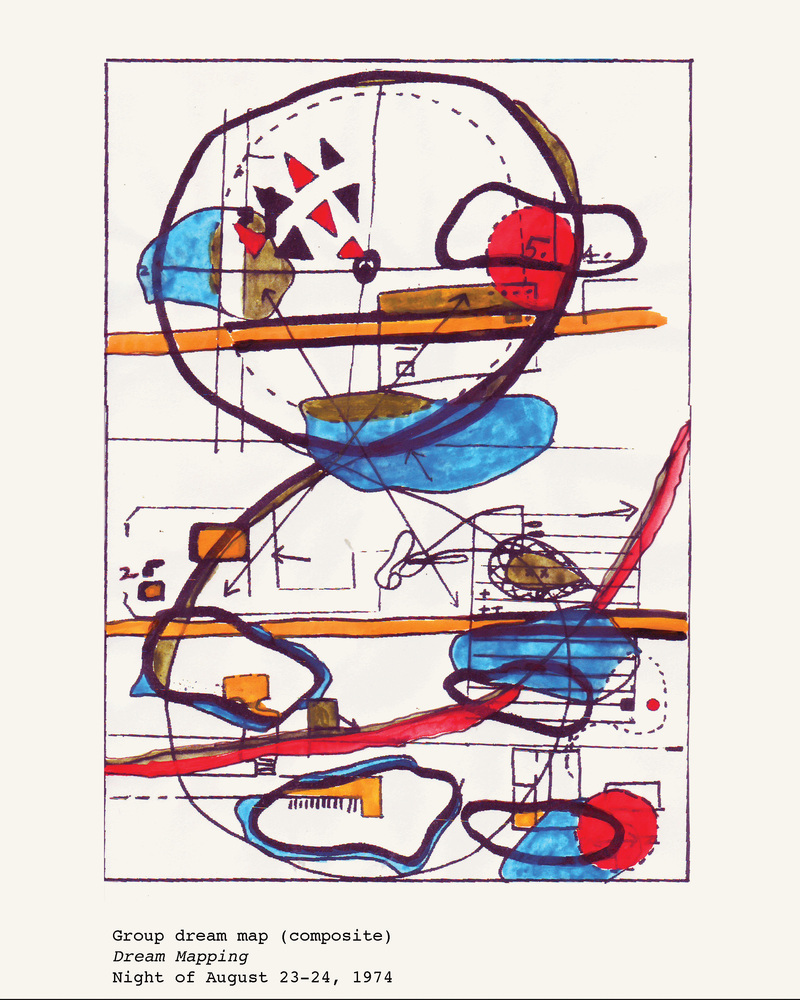

Dream Mapping—Susan Hill

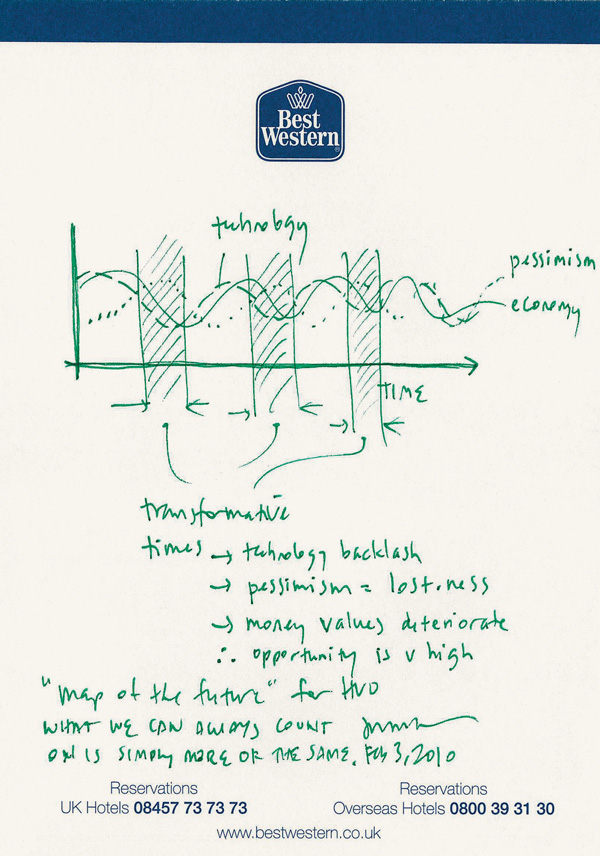

Map of the Future—John Maeda

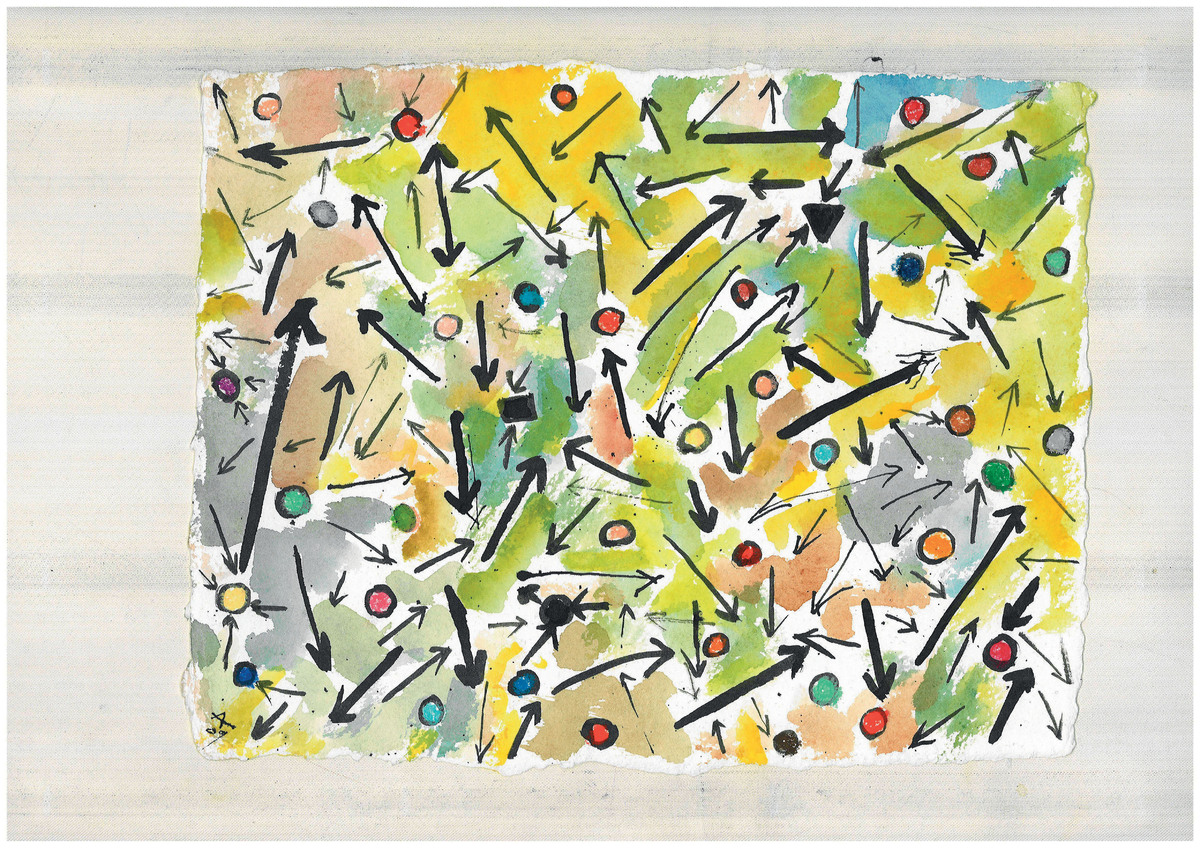

Forecast From an Artist—Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla

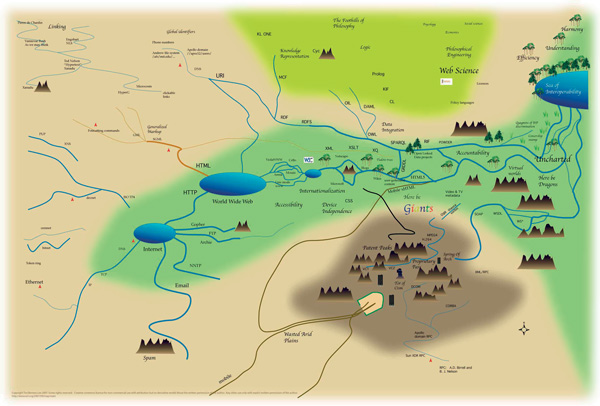

‘Mapping analogy for explaining to people the mingling and evolution of influences in the World Wide Web technology’—Tim Berners-Lee

(Source—Mapping it Out: An Alternative Atlas of Contemporary Cartography—Hans Ulrich Obrist)

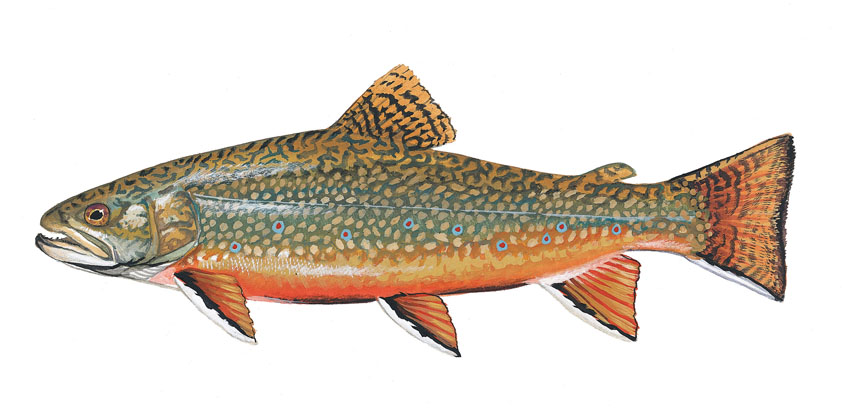

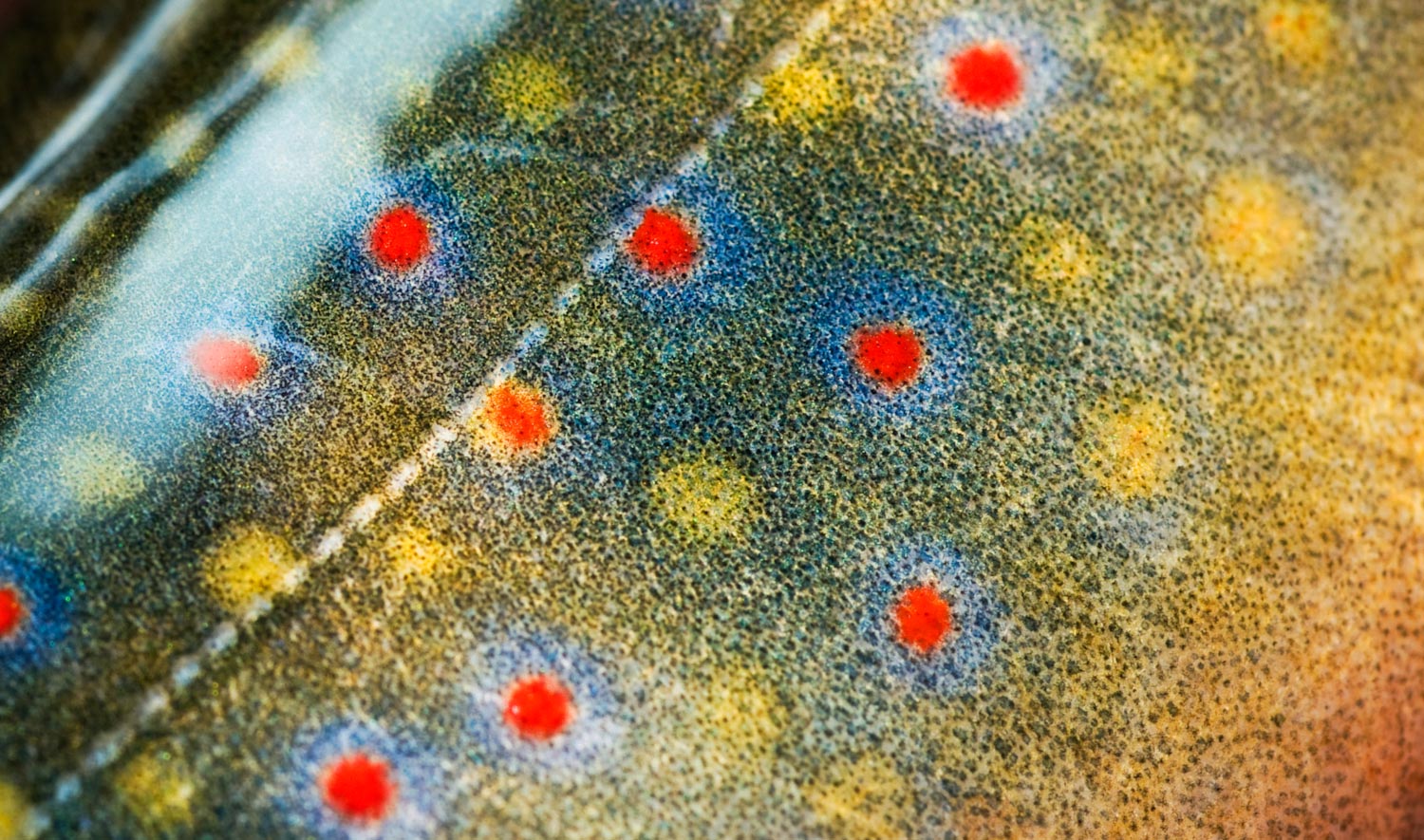

Brook Trout

Brook trout are members of the char subgroup of the salmon family (Salmonidae) which also includes the Arctic char, bull trout, Dolly Varden and lake trout. Char are distinguished from other trout and salmon species by the absence of teeth in the roof of the mouth, the presence of light colored spots on a dark colored body, their smaller scales, and differences in skeletal structure.

Also known by the vernacular names “native trout” or “natives”, “brookie”, speckled trout, and brook char, the species name fontinalis means “living in springs”. Brook trout have cooler water temperature requirements than the non-native brown and rainbow trouts.

(Source: National Park Virgina—Brook Trout)

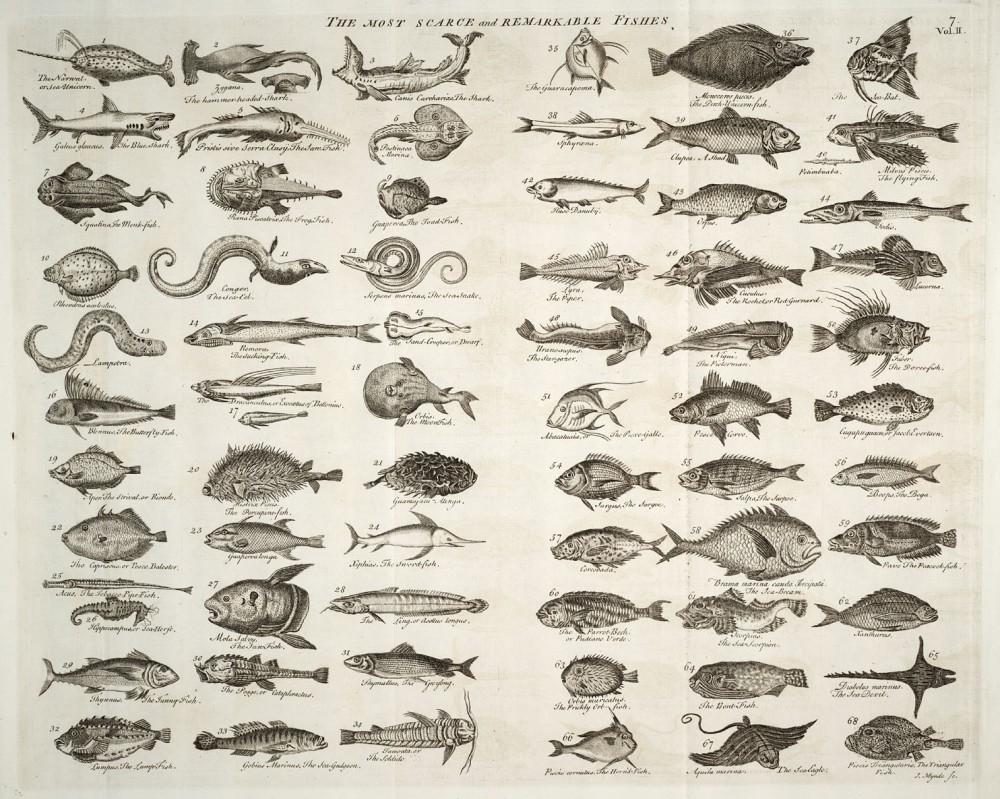

The Most Scarce and Remarkable Fishes

Chambers, Ephraim, 1680 (ca.)-1740., et al. / A supplement to Mr. Chambers’s cyclopædia: or, universal dictionary of arts and sciences. In two volumes (1753)

(Source: The University of Wisconsin Digital Collections—History of Science and Technology)